When the so-called loudness war raged between 1990 and 2010, limiters and audio compressors hit new highs in popularity among producers and audio engineers. It became the norm to reduce the dynamic range of tracks not for artistic purposes, but rather to crank the level of productions up to the limit. Loudness standards and streaming platforms finally brought a halt to all of that.

During the loudness war, artists and producers as well as listeners began to complain about this pointless competition for loudness until things finally started to change. Where trying to make tracks louder than the competition had once been the most important objective, giving a track the right dynamic range is now the goal. Although the importance of dynamic range in music experienced a revival after a loudness peak around 2005, it was the rise of streaming platforms like Spotify, Tidal, YouTube or Apple Music and their use of loudness normalization that finally put an end to the war on loudness.

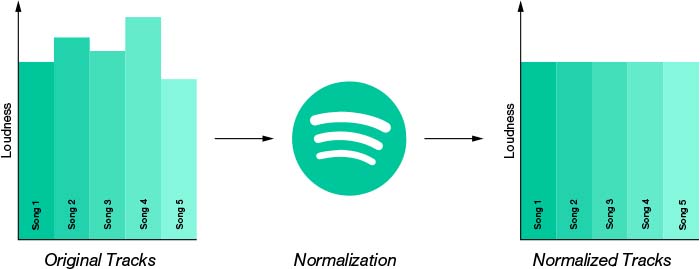

Streaming platforms want their listeners to have a smooth and consistent listening experience while browsing through their music – even when they constantly jump between different artists, albums and genres. One crucial factor that guarantees a smooth listening experience is having similar loudness across consecutive tracks so that listeners don’t have to fiddle with the volume and can simply enjoy the music.

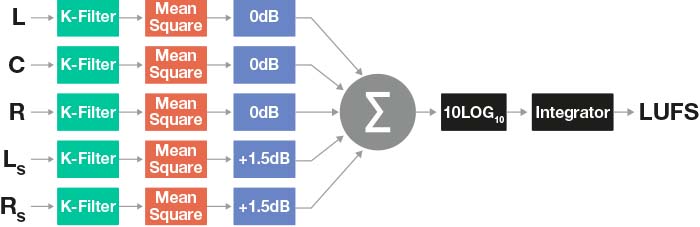

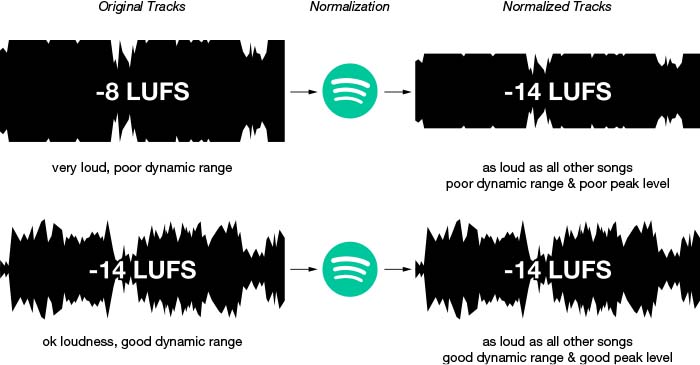

To achieve a constant streaming loudness, platforms apply so-called loudness normalization to all tracks that are uploaded: They turn down (some platforms also turn up) tracks that are louder (or quieter) than a certain reference loudness value. This value is typically given in LUFS (Loudness Unit Full Scale), a scale representing the perceived loudness of an audio track. Hence, tracks with the same integrated LUFS value (= measured over the whole track) are likely to be perceived as having the same loudness by a listener.

A lot of producers assume that they have to produce every track to exactly hit a streaming platform’s reference loudness (e.g. -14 LUFS for Spotify, YouTube, Tidal and Amazon Music). Otherwise, their track will be turned down (or up) by the platform and this has to be a bad thing, right?

Wrong! (in most cases)

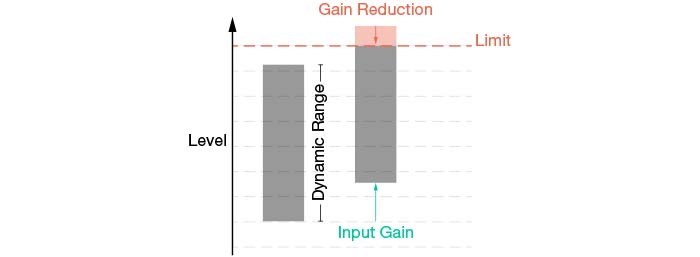

Remember: Every track is normalized to the same perceived loudness level, meaning that no track is louder than another after normalization. Yes, streaming services will turn a track with a loudness of -11 LUFS down by 3 dB. But this is simply a clean gain reduction that makes sure that the track is as loud as all the other tracks. It does not have any impact on the carefully crafted dynamic range or the characteristics of the track. It’s like turning down a playback device – hence, there’s nothing to worry about.

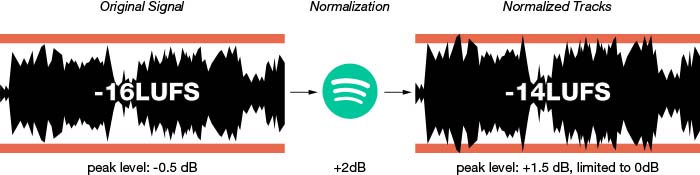

But why do we say “in most cases”? That’s because loudness normalization can have an unwanted impact on your track if the integrated loudness is below the reference loudness of a streaming platform. Let’s say a track with a loudness of -18 LUFS is uploaded to Spotify. In this case, the track will be turned up by 4 dB to make it as loud as all the other tracks. However, this can be a problem, since turning up your original signal by 4 dB will most likely cause the the gained signal to exceed 0 dBFS – and in this case an automatic limiter will be applied. Other platforms do not turn up tracks that are too quiet, but this is also a problem since your track will fall below the loudness level of most other tracks, which has a detrimental effect on the perceived track quality.

The dynamic range is what makes for transparency and let’s your track breath. That’s why tracks with a well-crafted dynamic range sound more lively and punchy than overly compressed songs. At the same time, tracks without any dynamic processing will quickly fall apart due to huge differences in loudness between different sections. As well, these tracks will sound bad on playback systems with a limited dynamic range such as mobile phones, laptops or small Bluetooth speakers. Therefore, it’s all about the finding the right balance in taming the peaks and loud parts of your track while letting the music breath.

Limiting is typically the final step in audio production and it allows you to fine-tune this balance. It correlates dynamic range and loudness: The more gain you apply to your signal, the more the peaks are limited and the narrower the dynamic range becomes.

Some genres like EDM, HipHop or Pop not only take harder limiting better than genres like Classical, Jazz or speech, they are even characterized by a narrower dynamic range. So, you basically have to keep all of that in mind while fine-tuning with a limiter: Dynamic range, genre and loudness requirements of streaming services. (Note: We are talking about limiting for publishing purposes and not as a creative effect.)

When preparing a track for publishing, some people tend to feel more comfortable with concrete values that tell them exactly what they should do to be sure that no streaming service, platform or publishing medium will “damage” their tracks. And while there are a lot of numbers and hints out there, simply focusing on achieving them often doesn’t work with your creation. As always in music production, things are rarely set in stone. That’s why we suggest the following simple guideline: